THE KINTYRE

ANTIQUARIAN and

NATURAL HISTORY SOCIETY

MAGAZINE

Issue Number 73 Spring 2013

CONTENTS

- Editorial Notes

- Missions abd Mysteries: U-Boats Round Kintyre- Ian Wilson

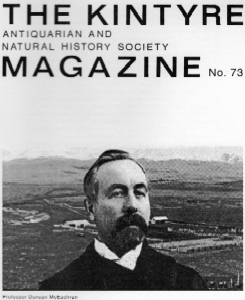

- Duncan McEachran: Kintyre's Most Famous Veterinarian- Ronnie Roberts

- Smerby Castle and its Historical Associations- Angus Martn

- Naomi and the Fishermen- Moira Burgess

- The MacAlisters of Tarbert- Archie K Smith

- Kintyre Wheelers Cycling Club- Agnes Stewart

- Obituary: Ken Holland- Susan E Holland

- Coincidences- Tommy Ralston

- By Hill and Shore- Angus Martin

- Book Review- Moira

Burgess

Kintyre Places and Place-Names; Angus Martin

This winter has brought the deaths, close together in time and place, of two stalwart supporters of the Society, Ian MacDonald and Ken Holland. Ian was Honorary President and Ken Honorary Vice-President, so within a matter of weeks these positions were emptied. A fitting tribute to Ken, by his daughter Susan, appears in this issue, while that to Ian has been promised for the following issue.

The author of this issue's leading article, Ian Wilson, will welcome any local information on naval wrecks off the Kintyre coast. His e-mail address is: duffel.coat@tiscaIi.co.uk

Our February talk, on dragonflies and damselflies in Argyll, was by Pat Batty, who is well-known among Kintyre botanists. Her interest in dragonflies wasn't so well-known, but became apparent as her talk progressed. Also apparent was the relative dearth of records for Kintyre, which she is naturally, as Scottish recorder for The British Dragonfly society, keen to rectify. Her address is Kirnan Farn, Kilmichael Glen, Lochgilphead P A31 8QL; e-mail: dragonfly.batty@gmail.com. She recommends The British Dragonfly Society's website at www.britishlragonflies.org.uk as a means of identifying species.

Our President, Murdo MacDonald, is researching the subject of bridge-building in Kintyre from the minutes of Commissioners of Supply of Argyllshire, who administered the county's 'bridge money' and engaged and supervised the builders. This spring, he will also be looking at bridges throughout Kintyre, with a view to writing an article for the magazine and giving an illustrated talk to the Society on the subject, and he is keen to hear from anyone who has information on or pictures of local bridges. His address is Balliemore, Castleton, Lochgilphead P A31 IRU, and his telephone number 01546 602667.

Moira Burgess is also writing an article for the Magazine, on K. Martin's Bookshop, 'a much-loved institution from its opening in 1901 until its closure in 2012', as she says. She would very much like to hear from readers who have information on or memories of the shop, its stock or its staff over the years. All material will be acknowledged on receipt and in the article. It can be e-mailed to moiraburgess@hotmail.com or posted to Flat 1/2, 260 Crow Road, Glasgow G II 7LA.

A review of Alex McKinney's long anticipated history of football in Campbeltown, Kit and Caboodle (Kennedy & Boyd, £14.95), will appear in the next issue. In the meantime, I recommend it as a 'must' for fans.

Finally, a celebration of the life and work of Naomi Mitchison will take place in Carradale Village Hall from 10 to 12 May. The accompanying exhibition will be open to the public on Saturday of that week-end and on Monday, Wednesday and Friday afternoon of the following week. Details of events are available in Campbeltown Library.

Ronnie Roberts

Duncan McNab McEachran was born in Longrow, Campbeltown, in 1841. He was the son and grandson of Campbeltown blacksmiths and farriers. The name McEachran is derived from Gaelic Mac Eachthighearna, 'Son of the horse-lord',1 and Duncan's line, the McEachrans of Killellan and Pennygown, were farriers, blacksmiths and farmers. His father was David McEachran, master blacksmith and a senior baillie of the town, who, according to the 1851 census, also farmed and employed four men. The business was located on the comer of Longrow and Corbett's Close (now Burnbank Street) and the family also lived there.

David McEachran's first wife, and Duncan's mother, was a Miss Jean Blackney. Little is known about Jean, who died in 1861. The name Blackney is not found in any other Kintyre records and is associated with the village of Blackney, near Wareham in Dorset. David married again to a Miss Marion McCallum, from Arran, with whom he had a son Charles. Both Duncan's brother William and half-brother Charles followed him to Canada and into the veterinary profession. Charles, in particular, married well. His wife, Margaret McPhee Allan, was daughter of Sir Hugh Allan, owner of a large Atlantic shipping line. Charles went on to become a very popular and successful Canadian businessman and a racehorse owner (naturally his horses were also successful - he was, after all, a McEachran!) Duncan McEachran was proud of his Kintyre lineage. He wrote several articles and papers on the fortunes of the Kintyre diaspora in Canada and called his home, in Quebec, Killellan.2

Duncan McNab McEachran was named after the Rev Duncan McNab, the minister of the Highland Parish Church who led his congregation out of the Church of Scotland in the schism of 1843.3 David McEachran was a strong supporter of McNab, who was a very charismatic man, and the dissenters established a new Gaelic Free Church at Big Kiln (later Lorne Street Church and now Campbeltown Heritage Centre). As well as the creation of two new churches on the site, one for Gaelic and one for English worship, the dissenters also established a new school. It was here that young Duncan McEachran was schooled in English, Latin, Greek, French, Navigation, Mathematics, Book-keeping and Geography.

In 1858, at the age of 17, Duncan McEachran entered the Edinburgh Veterinary College. This was a privately owned college and at that time the only one in Scotland. It is now known as the Royal (Dick) Veterinary School after William Dick, its original owner and one of McEachran's teachers. At that time, Diplomas from Dick's college were awarded by the Royal Highland and Agricultural Society, but before a student could practise professionally he was required to sit the examinations of the London-based Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons, a body licensed to the Privy Council and responsible for the 'uniportal' system entitling the use of the professional qualification MRCVS.

The period when McEachran was in Edinburgh was one of some turmoil in the veterinary profession and especially in Edinburgh. William Dick had originally trained as a farrier. In London he had attended extramural anatomy lectures, but that was all he had done before coming back to Edinburgh to set up his college. He was recognised as a good surgeon and a great proponent of bleeding and firing lame horses, but was no scientist. He did not believe in the germ theory of disease which was becoming accepted following the work of Pasteur and Lister and in this he was in conflict with his staff. His colleagues Gamgee and McCall strongly supported the germ theory and both left in disagreement over his views on treatment of the cattle plague outbreak in Scotland, and established their own colleges, in Liverpool and Glasgow.4

McEachran was of a very logical, scientific bent and was persuaded by the germ theory of Pasteur and Lister and the idea that human and veterinary disease conditions represented a continuum of 'one medicine'. This, combined with an inherent stubbornness and inflexibility, made him less than popular with Dick. In 1861 Dick was asked to nominate a suitable young graduate to take up the post of first Director of a Veterinary college in Ontario. He had two candidates: Andrew Smith, a dull, hard-working plodder from Ayrshire, able, reasonable and capable of compromise, and Duncan McEachran, brilliant, idealistic, stubborn, with strong opinions, and a 'germ theory man' with a 'guid conceit of himsel'. 'Although McEachran was probably the more able, Dick chose Andrew Smith instead.

No doubt angered at being passed over in this way, McEachran travelled to Canada under his own steam and established a practice in Woodstock, Ontario, not far from where Smith's college was situated. Once there, McEachran did some teaching in materia medica for Smith and in 1867 they even published the first Canadian veterinary textbook The Canadian horse and his diseases, which went to two editions. However, they had very different philosophies on veterinary education ~d science. McEachran believed in high entrance requirements and science-based teaching. Smith, as the proprietor of the commercially-based college, pragmatically accepted students from anywhere if they could pay the fees and he firmly believed they should be taught, like apprentices, by practical training. 5

McEachran stayed only a few years in Woodstock, but during that time he met and subsequently married Esther Plaskett, the daughter of a wealthy farmer, who also had investments in sugar plantations in the Virgin Islands.

In 1865 he moved to Montreal where his friend John Shedden had a major cartage business and many horses requiring veterinary attention. He specialized in horse practice, as was the tradition of the day, especially for the son and grandson of farriers. Possibly even more significantly, he was one of the McEachrans, who were always known as 'the horse people'. He gained an excellent name for his equine skills, but, in keeping with his belief in 'one medicine', McEachran was also interested in diseases of cattle and pigs, and wrote a number of articles and reports on the. major infectious diseases affecting Canadian livestock. The McEachran practice in Montreal prospered and indeed it still operates, the oldest veterinary practice in Canada.6

John Shedden was well connected politically and introduced the upwardly mobile and ambitious Duncan to other major Scottish businessmen in Montreal, such as leading banker Donald McGill, Donald Smith (later Lord Strathcona) of the Hudson's Bay Company and Hugh Allan of the Allan shipping line. These relationships served McEachran well and he was proud of his Scottish and particularly his Kintyre connections.

Although travelling widely, McEachran based himself in Montreal for the rest of his life. He was active in the highest social circles and particularly active in horse matters, judging as widely as the New York and Chicago World Fairs. He and Esther had two daughters, but one died aged five. The other married, but her only child, a son, was born blind.

In 1866, McEachran decided to set up his own veterinary college based on the principles of scientific training and high entrance requirements. This was at a time when Canadian agriculture was already beginning its excellent reputation for stockbreeding, particularly in the dairy industry, and McEachran was one of its leaders. His Veterinary School was closely aligned to the world famous McGill University from the start, and was the first in the world to demand educational qualifications, and not just ability to pay the fees, from his students. So high were his entrance and qualification standards that in the first nine years only ten students graduated. Such was their ability, however, that the school became recognised as the best in North America, if not the world, at that time.

In conjunction with the world-famous medical epidemiologist, Sir William Osler, he also established the requirement for his students to take courses in the medical school as well as in veterinary classes and he is generally considered one of the founders, with Osler, of the scientific discipline of Comparative Pathology. His educational philosophy, which was based on the similarity between human and animal medicine, required his students to take courses on basic science as well as training in pathology and clinical experience. In this they anticipated the teaching model that most Western schools of veterinary medicine would adopt subsequently. It is still the basis of 21st century veterinary teaching courses throughout the world, but few are aware that one of the pioneers of modem veterinary education was a blacksmith's son from Longrow, Campbeltown.

In 1874, through the influence of Sir William Osler, McEachran's college was absorbed into McGill University and McEachran appointed Dean of Veterinary Medicine, a position he retained until his retirement in 1903. In 1905 he was awarded the honorary degree of D.Sc. by that University in recognition of his contributions to scientific education. Eventually, the costs of maintaining a veterinary school within the medical faculty and competition from the French-speaking college forced McGill to close the school, but it had by then made a firm contribution to both raising standards and emphasising the close relationship between animal and human diseases.7

McEachran's contribution was not restricted to science alone, however; among his other achievements were the introduction of a quarantine system for Canada, which is still the basis for one of the highest standards of animal agriculture in the world, and the establishment of a control system for the horse influenza epidemic in New York, which in the 1870s was paralysing the city's transport system. Because of his advocacy and development of animal health policy and regulations, leading to the first national health regulations, in 1885 McEachran was recognised by the country's political leaders and became the first chief veterinary adviser to the Government of Canada. So successful were his import controls, that they became a model for other countries, and for his contribution to national policy development McEachran was awarded the honorary degree of LL.D in 1909.

Duncan McEachran's life was not confined to academia and veterinary practice, however. He undertook Government missions in support of the Canadian agriculture industry, especially in relation to the need for enforcement of international quarantine laws, and also acted for wealthy Canadian investors in importing high quality pedigree cattle and horses from Scotland.

In this task he visited Scotland regularly and often used the opportunity to visit Campbeltown to purchase good Clydesdale horses from the best Kintyre breeders. In 1910 alone, he transported 10 Clydesdales from Kintyre breeders, including two from A. Ronald, Pennyseorach, and one each from Langa, Dalrioch and Uigle.8 It was on one of these visits that he decided that the inscription on the Campbeltown Cross, which had been erected, he believed, by one of his antecedents, should be reproduced with a translation from the Latin on a bronze plaque. These plaques are still to be seen on the plinth of the Cross, located at the head of the Old Quay at Campbeltown harbour. He also involved himself in using his political influence to secure leases and advise investors who were starting to ranch in the Western Provinces of Canada. In particular, he became a Director of the Cochrane Ranch Investment. Coincidentally, the name Cochrane in Kintyre can be an anglicisation of McEachran, but it is unlikely that he had any relationship to the principal shareholder.

During this time he also became involved in native Indian politics. Sitting Bull of Custer fame had fled to Canada, and McEachran tried unsuccessfully, on his behalf, to negotiate conditions of safe return to the U.S.A. He also carried out deals for the Indian tribes of the west, as he had great influence with Government, and for these he was made a chieftain of the Blackfeet tribe, known as Chief Akotas.9

McEachran's dour Scottish manner, however, led to difficulties for him with his fellow directors in the Cochrane ranch, and this, coupled with serious losses due to abnormal winter conditions, led to his exit from the company. Not daunted, he immediately involved himself with another ranching company, the Walrond Ranch, some 260,000 acres, funded by wealthy English investors.

Possibly one of McEachran's most important and most financially successful involvements, however, was in the Anaconda mining saga. Anaconda was a large US mining company which, among other things, mined and smelted copper in a very large open-cast location in Butte, Montana. Toxic fumes from the operation, however, led to significant cattle losses in farms to windward of the factory. The company compensated the farmers and remedied the problem by constructing very large chimneys and modifying their discharge patterns. Unfortunately for them, however, as is often the case when farmers are compensated and lawyers get involved, other farmers from a very wide area started to make massive claims of doubtful validity. The share price of Anaconda was severely affected and the Board decided to defend their actions. They made enquiries and announced that ' ... a clever Scotchman called McEachran has been hired to save the business'. McEachran organised a defence replete with distinguished expert witnesses who demolished the farmers' case. It was the first time that such a defended case using extensive expertise had been led and McEachran received great plaudits. The share price of Anaconda recovered and naturally McEachran received a very significant and well-deserved fee.

One of his last successes, and one which was no doubt very close to his heart, was in winning the argument with the French farming lobby in Quebec, who had received a Government subsidy for the importation of French Percheron horses in preference to Clydesdales. McEachran was asked by the Clydesdale supporters to intervene with the Government. Through his political connections and his depth of experience of horses and the qualities of both breeds, he managed to persuade the Government to lift the subsidy and as a result the breeds competed on an equal footing.

Duncan McNab McEachran died on 13 October 1924 in Quebec. One obituary refers to him as o An irascible old Scot known throughout his life for his inflexible attitudes, abrasive nature and impatience with the inferiority of lesser mortals, but also a genius whose immense contribution to agriculture, to veterinary medicine and to the development of Canada has never been properly recognised' .10

Duncan McEachran remained a man of Kintyre to his death. In his will he left a large sum, from the interest of which his wife, daughter and grandson were to receive an annuity equating to the present-day equivalent of almost $200,000 a year.

However, possibly because of his dislike of his son-in-law, he was adamant that nothing was to be left to direct descendants (if any) thereafter and all remains of the estate were to go back to CampbeItown for his FULL brothers and sisters and their descendants. His grandson, the blind Harrison McEachran Young, died in 1977 in Vancouver Island. Unfortunately, although Canadian lawyers contacted the Campbeltown McEachrans at that time, the money apparently was no more.

Much of the information in this paper is derived from discussions with Sadie Galbraith Muir, an eminent Kintyre genealogist, and Angus Martin in CampbeItown. P. David Green, a retired Government veterinarian in Victoria, Canada, whose definitive biography entitled Visionary Veterinarian: Dr Duncan McNab McEachran, is currently in press, has also been most helpful. His outstanding text will add greatly not only to the story of McEachran and his brothers but to the history of animal welfare, biosecurity and veterinary medicine in Canada and beyond.10

- 1. Black G. F. (1999 edition) The Surnames o/Scotland: Their Origin. Meaning, and History, New York, p 489.

- 2. P. David Green, pers. comm.

- 3. Rejecting Scotland's Establishment, in www.Knapdalespeople.com

- 4. Yam P., Editor (2012), Glasgow Veterinary School 1862-2012. University of Glasgow Press, p 10.

- 5 Goulet G. & Jean F., 'Duncan McNab McEachran (1841-1924)', Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online, www.bio~raphi.ca

- 6. Mitchell C. A. (1966), 'Canada's oldest veterinary practice'. Canadian Journal of Comparative Medicine and Veterinary Science. 30:287-289.

- 7. Derbyshire J. B. (2012), 'Contributions by British graduates to early development of veterinary medicine in Canada'. Veterinary History. 12: 290-291.

- 8. Martin A. (1984), Kintyre Country Life, Edinburgh, p 63.

- 9. Martin A. (2011), Kintyre Families, Campbeltown, p 35.

- 10. Pers. comm., Mrs Judith McAlister, Campbeltown.

Archie K Smith

This important branch of the Clan Alasdair emerged in the early 16th century. Their landholding was extensive. From the Tarbert base, it stretched northwards up the coast of Loch Fyne. This led the local writer of the First Statistical Account to describe them as 'by far the most considerable family in South Knapdale'. However, their origin was the Kintyre MacAlister family of Loup. In 1532, the current laird, Black John, signed a Bond of Fealty to the Earl of Argyll. This nobleman had become considerably more important locally owing to wider changes. After spending much time and energy on the affairs of the West Highland part of his realm, King James IV decided to put the problems of law and order into the Campbell Earl's hands.

On the Earl he bestowed a 'commission of Lieutenantry, with fullest powers over the Lordship of the Isles'. Associated with that wider remit, the Earl became Keeper of the Royal Castle at Tarbert and Baillie and Governor of the King's Lands in Knapdale. His presumed reward was the creation of a feudal Barony of Tarbert in his favour. Those changes appear to date to around 1499.

Perhaps as a result of the Bond of Fealty, Donald MacAlister, second son of the Laird of Loup, was appointed Constable of the Castle. His recompense was the grant of the extensive lands to him and his heirs and successors in office. Donald became the first MacAlister laird of Tarbert. As well as the defence of the Castle, Donald was required to keep it wind- and water-tight. The other obligations were concerned with giving hospitality to the King and the Earl and transporting them by sea over a defined area of Loch Fyne.

The second laird of Tarbert was Charles, Donald's son. He, in his own right, was granted a charter of former church lands by his cousin Alexander, Vicar of Kilcalmonell. The main part was the two merkland of Balinakill.

The third laird was Hector. He is known to have been living in the Castle in 1580. He had feuds with his neighbours in Arran and was later imprisoned for his misdemeanours.

The fourth laird was Archibald, who was the first to be designated 'Captain' of Tarbert Castle. While still designated 'younger of Tarbert', he, with three other lairds in Knapdale, raided Bute in 1602. This was a military expedition of 1200 men. In 1631, he made a more pacific journey to Stirling to visit a distinguished relative, Sir William Alexander, Earl of Stirling.

The fifth laird was Godfrey. He was in action across the Clyde against landowners on the mainland of Renfrewshire and Ayrshire. He later became Depute Admiral of the Western Isles, responsible for the safety of the fishing fleets and other important functions including resisting foreign invasions.

The sixth laird was Ronald, a man of more peaceful times. He became a member of the Commissioners of Supply of Argyll, who administered all local government affairs and were responsible for the building of bridges, houses and piers, together with many other improvements. Ronald's name is specifically mentioned in 1664 and 1668 in relation to projects for the Tarbert area.

The seventh laird was Archibald, second of that name, who succeeded in 1685. He too looked south to the fairer lands of Kintyre. He purchased Balinakill Estate, and other lands, in 1698. Like his father, he was not involved in strife; however, he was required to compile a list of 'Fencible Men' on his estate in 1692 for the Sheriff of Argyll. The fighting in Ireland might have moved to Argyll, but thankfully did not. Unlike his neighbours, he listed the men under his separately named lands, so producing an inventory of them. As listed, they were Craiglassen and Daill, Achendaroch, Brackley, Kildusculand, Ardrishage, Atuchuan, Breanfforlin, Iurelines, Achines, Barmore, Ye merkland of Tarbert, Glenrolich and Balymeanoch, and Glenaickill. This Archibald might be called the first improver laird of the Tarbert area (a title later bestowed on the lairds of Stonefield Estate). He was responsible for two Acts of Parliament which were to produce changes lasting to the present day.

The first was the 'Act in favour of Archibald Mackalester of Tarbert for four weekly fairs and a weekly mercat at the Toun of East Tarbet'. The fairs of two days' duration were to be held on 10 May, 16 July, 19 August and 16 October, and the weekly markets to be held on a Tuesday. The second was of greater importance. It gave the bay designated East Loch Tarbert the status in law of a harbour. The body running it was to be able to levy charges for structures - the genesis of today's Tarbert harbour.

The eighth laird was Charles, who succeeded his father. He farmed on an extensive scale. He rented several large farms on the island of Islay and also farms in Kintyre from the Duke of Argyll, and these were retained by his son after he died. During his lifetime, Charles made strenuous efforts to bring education to the Tarbert area. He petitioned the Synod of Argyll for help in 1724: 'In the town of Tarbat there are two hundred examinable persons who have many children very fit for school but are so poor that they are neither able to send their children to any place where education be had, nor maintain a Schoolmaster at the place but in order to encourage learning there your petitioner is willing to contribute for that purpose something and it is expected that the Reverend Synod will, out of their public fund, give assistance for so good a design which must fail should they deny it. '

Charles's death is recorded on a marble slab on the wall of the MacAlister burial vault in the oldest part of the Old Tarbert Cemetery. His death, which is recorded as occurring on 3 April 1741, was to mark the end of an era for the family. To meet the family's debts, his father had disposed of most of the lands from the north end of the estate southwards. Charles, by his fanning enterprise, had held the line and left his son the ultimate problem.

The ninth laird was Archibald, third of that name. He was to be the last of the line. Writer after writer states that he sold the Tarbert and adjoining lands to Archibald Campbell of Stonefield Estate, his neighbour to the south, in 1746. However, a valuation roll of Argyll of 1770 shows Archibald MacAlisyter as still having 'Tarbert tenement in Tarbert' (the Castle?) and also, north of Tarbert, 'Old and New Ashens, Barmore and isles, pendicles, tiends'. A court action by the Duke of Argyll against the trustees of Archibald MacAlister is dated 1762 (the subject was the old feudal obligations connected with the Castle). The MacAlisters had left the Castle and built a large house at Barmore, which in 1748 had 33 windows. 'Lady MacAlister' was assessed for 24 windows in 1762. It may be that this Archibald MacAlister died before 1762 and that the remnant lands were held by trustees for his widow. They were to become part of the Estate of Stonefield.

In his book Tarbert in Picture and Story, published in 1908, Dugald Mitchell says of the MacAlisters: 'Though landless, many descendants of the family continue to live in the village and neighbourhood. Others have gone from the home of their fathers, and several fill honourable positions in the professions and other spheres. The brilliant career of Dr Donald MacAlister, appointed early in 1907 to the Principalship of Glasgow University, has been a source of liveliest interest and satisfaction to the good people of the village.' He was later to become Sir Donald MacAlister of Tarbert.

Ian MacDonald, during 1984-5, carried out research on the ancestry of this eminent gentleman. Summarised, the line of descent reads:

Archibald MacAlister, 9th Laird of Tarbert

John MacAlister and Ann Carmichael

Hector MacAlister and Janet MacFarlane

Donald MacAlister and Euphan Kennedy

Sir Donald MacAlister of Tarbert

The author acknowledges with gratitude the assistance of Mr Archibald MacAlister, Edinburgh, and the late Mr Ian MacDonald, Lochgilphead, whose researches he was able to utilise.

Moira Burgess

On a first glance at the title of this book you may think that you've been here before, since Angus Martin has recently re-edited and updated two booklets on Kintyre place-names (see review in Kintyre Magazine No. 66). Don't be deceived. This is something quite different: not only different from these booklets, but from any other book you have ever read.

I'll immediately contradict myself here. It may remind you slightly of Tim Robinson's writing on Connemara and the Aran Islands. Robinson's method is to wander around his island, stopping whenever a place or place-name strikes him, and describing, in leisurely fashion, an associated historical event, anecdote or nature observation. Though Kintyre Places and Place-Names is ordered alphabetically by Gaelic place-name elements - achadh, dun, maol, sron - there's the same effect of an almost casual erudition, disguising vast resources of research and knowledge.

This is a sturdy book of over 300 pages, and I began to read it, as you may like to, by dipping in (of course, there are comprehensive indexes) to find places I knew. There's Lochan Dughaill! I always wondered about that, since I couldn't see any lochan; now I know the answer. There's Bellochantuy, such a familiar place-name, which (it turns out) I've been explaining to people quite wrongly for decades. There's my favourite place-name of all, Bealach a' Chaochain, which I don't think I've ever seen written before, let alone explained. It might mean 'windy gap', or might refer to an underground stream, and there's even a glance at the possibility of a whisky-smuggling operation. Whatever it actually means, the very sound of the name brings that high, narrow, twisty bit of the West Road irresistibly to mind, and that's one of the gifts of this book.

A conscientious reviewer does eventually get down to reading the book straight through, as will you, and that's when its full richness is seen. There is history; we all know Angus Martin's achievements in the field of Kintyre local history. There are folk-tales and anecdotes, in which you can hear the voice of his informants, shepherds and fishermen now gone. There's genealogy, as you'd expect from the editor of the Kintyre Magazine, and natural history, from a man who has walked Kintyre hills and shores all his life. There are notes on Kintyre writers and bards George Campbell Hay, Naomi Mitchison, Dugald Macintyre, Willie Mitchell - and, all the more precious for its rarity here, the occasional snatch of Angus's own poetry, inspired by some comer of Kintyre. Amazing that this is not a work of collaboration; all these topics are facets of Angus's archival store and his questing mind.

And yet he'd be the first to object to that statement, rightly to some extent. His many sources are fully and generously cited. William J. Watson on Celtic place-names and Edward Dwelly's Gaelic dictionary are there, as you would expect, beside less well-known but invaluable local names. There are no fewer than 1573 references (is this a record?), tidily tucked at the end of the book, so that you can either chase them up or read through the pages undisturbed.

Above all, note the carefully worded title. "'Places" in the title of this book precedes "Place-Names"', writes Angus, 'and the order is deliberate ... I might also have added "People"'. This is the clue that what we have here is far from being the average book on place-names. The pages are full - as the now-deserted steadings and sheilings once were - of Kintyre people from the distant and the more recent past, working, fishing, farming, living hard but well. They played shinty at Machribeg; they killed a wild boar near Cour, when it was so disobliging as to eat a little girl. At Corrylach in Southend we learn of Willie Tait who was 'born to steal'. At Allt a' Choire Calum MacGeachy hears an uncanny voice greet him, 'Ho! Calum!', but silences it by mentioning the Blessed Trinity. At Creag Ruadh near Killean a mysterious hand-mill is wont to work all on its own: 'I hear it often enough,' reports Grandfather placidly, 'but I've never come on it goin.' And all those stories were told round the peat fire to the five or six or seven children in a family, whose names we know because they're in the census, but who come to life here.

Angus remarks: 'Dùn is a little word which sits on top of an immense heap of history, most of it out of reach.' The same could be said for most of the place-names in this book. Angus Martin's achievement is to use them to bring the history and people and scenes of Kintyre, delightfully, within our reach.

Copyright belongs to the authors unless otherwise stated.

It organises monthly lectures in Campbeltown - from October to April, annually - and has published its journal, 'The Kintyre Magazine', twice a year since 1977, in addition to a range of books on diverse subjects relating to Kintyre.

CLICK HERE for Correspondence and Subscription Information.

ISSN 0140 0762