THE KINTYRE

ANTIQUARIAN and

NATURAL HISTORY SOCIETY

MAGAZINE

Issue Number 92 Autumn 2022

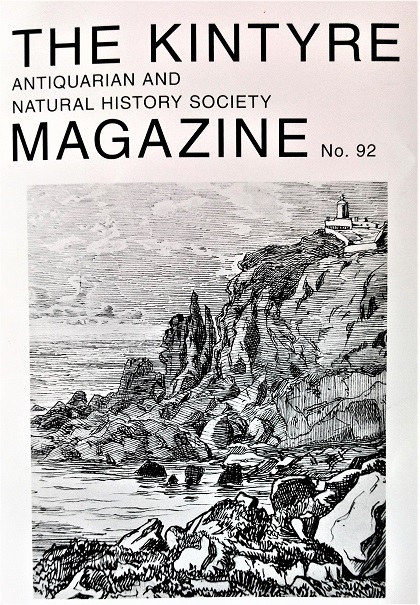

Cover illustration:

Mull of Kintyre and Lighthouse, c 1866,

from the sketchbook of Captain T. P. White in possession of John C Cunningham

CONTENTS

- Three Campbeltown Scotts; Angus Martin; inside cover

- Captain White, Ubiquitous Survey Sapper; John C Cunningham; P2

- Two Letters; 1853 and 1854; Charles Blair; P9

- Tarred With One Brush; Argyllshire Herald; P13

- 'Tragic Death of Zachary M. H. Ross'; Angus Martin; P14

- 'The Big Count in Campbeltown' (1931); Argyllshire Leader ; P18

- By Hill and Shore; Angus Martin; P20

- The Children's Graves at Mull; Allan Cadenhead ;P24

- The Beginnings of the Lighthouse; Ann Aikman Smith; P27

- Mull of Kintyre Lighthouse (1832); Rev Donald Kelly; P30

- Letter to the Editor; Murdo MacDonald; P32

- Editorial Miscellany; P33

Three Campbeltown Scotts

Angus Martin

The following biographical sketches are from my work-in-progress, Kintyre Families, and the sources contained within the original text have been removed.

Dr Joseph Scott, who died in 1939 at 'Dana', Virginia Water, Surrey, had been the leading ophthalmic surgeon in Iran and was honoured by the Shah. After a basic education at Millknowe School, he became an apprentice in Dr John Cunningham's druggist's shop in Campbeltown. Resolving, however, to become a doctor himself, he attended evening classes in town and then went to Glasgow University, where he graduated M.B., C.M. in 1894. After a period as medical officer of health in Basra, on the Persian Gulf, he returned to Britain for post-graduate courses and then established himself as surgeon to the Royal Hospital, Tehran. He mastered the Farsi language, travelled widely in the country, and, in the course of his work, 'acquired a unique influence in Iranian government circles' and a 'knowledge of political intrigues denied to most Europeans'. At a time when Russia, Germany and Britain were competing for influence in the region, his insights were valued at the British Legation, to which he was surgeon. He was doubtless the 'Dr John Scott' who donated 'Babylonian tablets' to Campbeltown Museum in 1902. His father, William, was a farm servant in Dalrymple Parish, Ayrshire, when he married Agnes McMillan in Campbeltown in 1853; in Census 1871, he was a fisherman in Shore Street with Agnes and five children, of whom Joseph, at eleven months, was the youngest. Dr Scott's wife, Sarah Jeffrey, died in Edinburgh in 1921.

His brother William was killed on 19 October 1897 at Busoga, Uganda, by 'Sudanese mutineers' and 'Mohammedan Buganda', while engineer of a steam launch 'plying Lake Victoria Nyanza'. The boat had been 'taken out by him in pieces' and reassembled. He had set out from Mombasa in September 1896 with seven or eight hundred 'native porters' and was 'well supplied with guns, revolvers and ammunition'.

In 1933, Robert Scott, a sportswriter with the Sunday Post, began reporting football matches on 'the wireless'. In 1934, he joined the Daily Record as its 'leading football writer'. His by-line, 'Captain Bob', derived from his army rank in the First World War. He was born in 1891 in Campbeltown to Robert Scott, Greenock-born painter, and Catherine McVicar, daughter of Donald, tailor in Campbeltown, and Eliza McIntyre. His father died when Robert was three years old, and his mother and her young family were forced on to the poor roll. Robert Sr. had gone to Glasgow on 3 December 1894 to work on the S.S. Refugio, which had been launched by the Campbeltown Shipbuilding Company and lay at James Watt Dock. He began work that same day, fell twenty feet down a hatch and died the following day in Greenock Infirmary.

A copy of his publication is on the internet

Captain White: Ubiquitous Survey

Sapper

John C. Cunningham

Thomas Pilkington White (1837-1913) is most famous for the publication of two fine volumes of archaeological sketches, the first covering the district of Kintyre, published in 1873, followed two years later by a companion volume covering Knapdale and Gigha. The research, writing and publication of both volumes took place between 1864 and 1874, for the greater part of which decade he was serving as an officer in the Royal Engineers stationed in Scotland. From accounts of the time, it is clear that he intended further volumes to be produced covering all of Argyll, but these never materialised, and he may even have had ambitions of working and publishing further afield.1

During a long and distinguished military career, he never returned to this work. The fact that his work caused considerable controversy at the time might go some way to explaining his reluctance to compile any further publications in this field. His two volumes have become much loved and respected contributions to history. Since little appears to be known about the author, this short article attempts to fill a biographical gap and place his work in context, both in terms of its mixed reception and the judgement of subsequent historians as to its value.2

Thomas White was born in Cheltenham in 1837, the fourth son of Thomas White, who was a senior official in the East India Company. He was educated at Cheltenham and then at Woolwich, from which he received a commission in the Royal Engineers in 1857.3 In 1862 he married Caroline, daughter of Mr H. H. Smith of Stourbridge, and early in his career he travelled to South Africa. In 1864 he was appointed to the Ordnance Survey of Scotland and in June of that year took over the Glasgow Division of Ordnance which was just commencing its survey of Argyll. After receiving this appointment, he leased The Manor House, Oban, where he and his family lived for much of his posting.4

When Lieutenant White joined the Ordnance Survey, it had been working in Scotland for well over a century, having been set up in 1747 in response to the Jacobite uprising in the Highlands. The plan was for the maps to help enable military infrastructure, such as forts and fortifications, to be connected by a new road network. Mapping of the whole of Scotland was complete by 1755, but over a hundred years later the military origins of the Ordnance Survey had been superseded by its clear economic and social benefits, though it still met some resistance from large landowners with a vested interest.

During the period 1862-1877, Argyll was mapped in the 25inch to a mile series, which included all towns, villages and cultivated areas. The principal area which was not included was the uncultivated moorland region which covered the central north of Kintyre. These maps were to prove fundamental to plans for agricultural improvement, water supply, boundary disputes and valuations. They are in themselves works of detail and beauty. Spot heights and permanent features were included but not contour lines. The survey was based on triangulation by teams of eight to ten men on the ground using chains and theodolites. Accurate heights were measured on either permanent features or spot heights.

Still only in his late twenties, White was not only responsible for the quality of the men's work but also for their pay, travel and quarters. Given that the whole of the area of Kintyre south of Campbeltown was included in the survey, this was a considerable undertaking. Work was problematical before April and after November owing to the severity of the weather. In 1870, Major General Sir Henry James, F.R.S., M.R.I.A. (1803-1877), Director-General of the Ordnance Survey from 1854 to 1875, wrote in an annual report to parliament: 'We must more generally adopt the system I introduced last year with surveyors in Argyllshire. They were brought down from Oban in a steamer in October and employed during the winter in Flintshire and Cheshire.'5

It is noteworthy that White's wider interests in archaeology were supported by Major General James, who was determined that where possible archaeological features should be identified on maps. In 1865 James issued an order stressing 'the necessity of officers' making themselves acquainted with the local history of, and (by personal inspection) with objects of antiquarian interest in the districts which they are surveying in order that all such objects may be properly represented on the plans and fully described in the Name Books'.

In respect of the survey in Scotland, this was putting into practice the request a decade earlier by the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 'that all remains, such as barrows, pillars, circles and ecclesiastical and other ruins' should be noted by the Survey. This was agreed with the proviso that the Society 'endeavoured on their part to assist the surveyors with local information through the co-operation of the resident gentry, ministers, school masters and others'. It is no surprise that though White's first volume was dedicated to Her Royal Highness the Princess Louise, Marchioness of Lorne, the second volume carried the following dedication: 'To Major General Sir Henry James R.E. F.R.S. Director General of the Ordnance Survey whose zeal in the cause of Archaeology has so materially contributed to the publication of these pages. This volume is inscribed with the author's grateful acknowledgement.' Without the endorsement of the principal landowner and of his military superiors, his work would probably have been impossible.

Details of his travels and work in Kintyre are sketchy, apart from what can be gleaned from his publications, which give some idea of his itinerary. He later wrote in general about the arrival of the Survey throughout the U.K: 'For, undoubtedly, there must be few among those residents in our islands, whether dwellers in town or country, to whom the sight of the ubiquitous survey sapper and his belongings had not long ceased to be a novelty. His station-piles have been visible for years past on all the principal mountain summits and hill ranges throughout the country. Scarcely a rustic bumpkin but has gazed, and then speedily forgotten his astonishment, at the network of cross-headed poles which have sprung up in every locality, on ridges and knolls, downs and uplands, riverbanks and sea-beaches, marking in succession the advance of the Ordnance Survey'.6

He clearly managed to combine his military surveying work with his archaeological sketching and historical enquiries. This detailed research required considerable assistance from local landowners and scholars. He was a skilled artist who took great trouble to locate and sketch monuments. He also provided landscape views of surrounding localities. During his work in Kintyre, he supervised the compilation of the Ordnance Survey Name Books, which document place-names and interpret their meanings, and these books often contain entries initialled or signed by Lieutenant or Captain White.7

In 1867 he left Argyll for a new appointment with the Ordnance Survey in Edinburgh, which limited his field work in Argyll but most importantly enabled him to present his work to the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland and locate a publisher. On 12 April 1869, he presented his first paper to the Society, entitled "Notice of Saddell Abbey, in Kintyre, Argyllshire; with its sculptured slabs'. This article was accompanied by four plates, detailing thirteen illustrations of stones, some of which subsequently appeared in his published work.

At the same meeting, James Drummond presented a paper titled 'Notes made during a wandering in the West Highlands; with remarks upon the style of art of some monumental stones of Iona, and other localities'. Unfortunately, the subject-matter of the two papers overlapped and Drummond was not going to allow others to address the Society without serious scrutiny of their work. He concluded his paper by saying: 'I would say a word to all who, like myself, are collecting drawings of these or any other class of antiquaries. Let all such be made lovingly and earnestly, adding nothing, leaving out nothing; but let every weather-worn feature, every chip, and every break be honestly jotted down. Of all things shun restoration. We all know how much easier it is to restore than to copy faithfully what we see before us; but it is only by proceeding in this spirit that such drawings acquire value to the antiquary, historian, and artist.'

If Captain White was in any doubt about Drummond's approach, the latter, having looked at White's plates of Saddell monuments, immediately identified a few inaccuracies which he highlighted to the assembled meeting, much to the discomfort of White, a relatively junior Society member, unlike his critic, who was a man of considerable standing. Drummond was an artist of national repute, with paintings in the royal collection, and a frequent contributor to the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, having been a fellow since 1848 and in recent years curator of the Society's Museum. He planned to publish his own work on monumental stones, and finding that White's work covered some of the same ground, his criticism might not have been entirely disinterested.8

If it was any consolation to Captain White, he was elected a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland in 1869. When he next addressed the Society, at its meeting in January 1871, he chose as his subject matter his method of preparing monumental drawings and dealt head-on with Drummond's criticism: 'Having had an opportunity since the last meeting of revisiting Saddell and making all necessary corrections in the drawings, the members of the Society will at a glance recognise the trifling extent of the alterations, by comparing the correct drawings with the prints from the originals.' At the conclusion of his paper, Drummond responded by claiming it to be a vindication of his criticism, 'having this evening shown his original drawings for that paper, since then corrected by comparison with the antiquaries themselves, and altered in almost every particular to which objection had been taken, thus showing the criticism was just and called for. He expressed surprise that his remarks the other evening should have been construed into anything of a personal nature.'

Any objective view can clearly see there were inaccuracies which needed altering. It was a salutary lesson in the importance of attention to detail and accurate draughtsmanship, and, whatever the circumstances, no allowance would be made for the hurdles which had to be overcome to produce his illustrations.

In May 1871, White addressed the same Society on the subject of 'The ecclesiastical antiquities of the District of Kintyre in Argyllshire'. This paper, and the earlier paper on Saddell, formed the basis of his first volume, which was published on 15 March 1873, Archaeological Sketches in Scotland: District of Kintyre, which his publishers, William Blackwood & Sons, of Edinburgh and London, advertised as containing '138 Illustrations with Descriptive Letterpress', of 'Imperial Quarto' dimensions, cloth-bound, and priced at £2 2s.

His book was overall well-received, apart from in The Scotsman, whose anonymous reviewer in April 1873 was scathing: 'In some respects indeed it falls short of attaining even such a level of usefulness as to entitle it to a place beside the local histories of humbler pretensions as a book of reference.' He concluded: 'Here the curtain may fall for the present. While we regret that it should be necessary to say so much that is disparaging of an author's first literary venture, we are bound to say, despite its defects, Capt. White's work bears indications of considerable ability, both literary and artistic, which we hope may be turned to good account. At the same time, it bears in its style too evident marks of haste, and slovenliness of composition, which he would do well to avoid in future efforts. It is a pity to see such an amount of honest hard work wasted in an attempt to realise an ambitious project. Captain White has forgotten the proverb fledglings should fly leigh.'9

This review, though unattributed, has the fingerprints of his adversary Drummond all over it. It was critical of the historic content and the illustrations, rather unfairly pointing out the difference between the illustrations shown to the Society in 1871 and those now shown in the published work. 'But when we find Captain White's newly published drawings of stones at Sadell vary from Captain White's drawings of the same stones, previously issued as illustrations to a paper of his on Sadell Abbey ... we do not feel comfortably convinced of the trustworthiness of the rest of the drawings Anything harsher, harder and more utterly destitute of artistic feeling than the effect produced on several of them, is impossible to conceive.'

Other newspapers were much more complimentary. The Guardian commented: 'We may safely pronounce this handsome volume to be not only a real ornament to the drawing-room table, but also a repertory of a large amount of curious information not easily obtained elsewhere in as accessible a shape, and an incentive to the pursuit of archaeology, as a study not only connecting us with the past, but important in its bearings upon the present and future of our race.'

On 8 December 1873, Captain White gave his final address to the Society on "The ecclesiastical antiquities of the district of Knapdale, Argyllshire and the Islands of Gigha and Cara'. At the end of this lecture, he informed his listeners that he had 'orders to go on a tour of foreign service' and this would be his last talk. In May 1874, he is recorded as commanding the 20th Company of Royal Engineers, which was making its way from Gibraltar to Bermuda. Prior to leaving, he completed preparations for publication of his second volume, though he wrote the preface and text in Bermuda in September 1874.

On 12 August 1875, Archaeological Sketches in Scotland. Containing Knapdale and Gigha was published by Blackwood's with 130 illustrations and a map. He responded in detail to The Scotsman's criticism, writing in the preface: 'A reviewer in a Scottish journal of standing and extensive circulation was pleased to charge me with two inaccuracies of detail in the plates of the last volume of sketches. The charge was totally unfounded; the explicit answer to it, and to some strictures upon other portions of the book, will be found in the opening chapter of the present volume.'

The whole of the first chapter of this second volume was dedicated to dealing with the article in The Scotsman, 'Knapdale & Gigha - Reply to a critic'. He uses the first fourteen pages of the work to deal line by line with The Scotsman's article of 9 April 1873. Reading the rebuttal, a century and half later, the anger in the words is palpable. Nobody could be in any doubt by the end of chapter one that Captain White took the criticism he had so publicly received as deeply personal. He concluded: 'Neither can I see any special reason for calling it ambitious; though, for the matter of ambition, being a soldier, I might remind my critic of Bacon's aphorism, that a soldier without ambition is a soldier despoiled of spurs in other words, no soldier at all.' It is worth pointing out that in this short sentence he refers to only one critic. He also emphasises the point that he is foremost a soldier, the clear implication being that he did this work in his own time and completed it under the most difficult of circumstances.

Of his second volume, The Scotsman was more complimentary: 'Captain White has practically exhausted the peninsula ... In this volume the author has thoroughly warmed to his work, and drives through it with an intensity that is quite inspiring ... A series of sketches, often racily written, of scenery and antiquities."

There followed his appointment in Bermuda, time in Malta and director of the Ordnance Survey for the Northern Division of Ireland. When he returned to Scotland in 1890 for his final posting, promoted to Colonel and commanding engineering forces north of the Tweed, the family lived at 28 Abercrombie Place, Edinburgh. His time seems to have been taken up with endless inspections and administrative work on the army estate, leaving little time for research or sketching. Surprisingly, there is no record of his having participated in the activities of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland during his final three years in Scotland.

He retired on 1 February 1894,10 aged 57, with an annual pension of £500, and lived in Torquay, Devon, until his death in 1913. After his work on Scotland in the 1860s, he never again wrote on Argyll history, but completed an influential and popular history of the Ordnance Survey of the United Kingdom, published in 1886 by Blackwoods. In addition, he wrote numerous articles about the Ordnance Survey and cartography for Blackwood's Magazine and The Scottish Review. Never a wealthy man, on his death he left his modest estate to his wife and two surviving children. ¹¹

His severest critic, James Drummond R.S.A., died in 1877 as a much-respected painter of Scottish history and an active and valuable member of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. His own work on monumental stones was published posthumously in 1881 as Sculptured Monuments in Iona & the West Highlands and printed for the Fellows of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. It was illustrated by his own exquisite drawings but did not include any illustrations from Saddell.

If his determination to ensure that others' field work was of the highest standards, he also directed his combative powers against other targets. In particular, he was a forceful critic of landowners who failed in their responsibility as custodians of the archaeological monuments on their estates, and those in Argyll who failed in their custodianship were called out publicly in no uncertain terms.

The verdict of history on Captain White's work has been kind compared to his initial critics. In the Argyll volumes for the Royal Commission on Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland, his work is regularly referred to. In Steer and Bannerman's work on Medieval Monuments, they state: 'White was deeply interested in antiquities, and during the time he was in the field he assiduously noted and sketched the ancient monuments that he encountered, particularly the ruined churches and graveyard memorials. The great majority of the late medieval carvings in Kintyre and Knapdale are described and illustrated in his two books and although the illustrations have no great artistic merit the decoration is usually accurately produced, being based in most cases on rubbings and tracings of the stones themselves.' In the plate section of the work, White's illustrations of Campbeltown Cross and three grave slabs were used.12

More recently, in Ian Fisher's Early Medieval Sculpture in the West Highlands and Islands, published in 2001, he states: 'Although less artistic than Drummond's drawings, White's engravings of carly and late medieval sculpture were more accurate in detail and for the first time were based on uniform scale, providing a comprehensive inventory of areas covered.' In fact, in this volume alone Fisher identifies two monuments drawn and described by White which have since disappeared. The quality of his work provided the building blocks for future academic research.Moving away from the academic to a broader view of Captain White's two volumes, it is fair to say they are works of extraordinary diligence and perseverance. Filled with valuable illustrations, they cover a wide geographical area, often difficult to access and involving weather which did not lend itself to outdoor sketching. He compiled and published a unique and superb record of monumental stones in Kintyre, which was not equalled until the publication, almost exactly a century later, of the Royal Commission's volumes.

He was on the receiving end of some trenchant and unpleasant criticism, especially of his first volume, but this did not deter him. In fact, he treated his critics with respect and good humour, writing in the opening chapter of his second volume, referring to a particularly scathing review: 'I am bound to add, not withstanding, that the review was written in a racy and slashing manner, with a certain pungent but piquant flavour not infrequent in that journal's literary notices; and although the general purport of the critique was decidedly adverse to the work under review, I was myself unable to resist its readableness. I remember an old saying of our school days, that the next best thing to giving another fellow a licking was to be able to take one, especially if it was administered in a tolerably capable manner. On the same principle, I am not to be considered as finding fault with the tone or observations of the review as far as they are just. I desire merely to rebut certain misstatements of fact and palpable exaggeration.'

His military work and posting provided him with the opportunity, but it was his own resolution of purpose and artistic skill which brought the project to such a successful conclusion. In this achievement, it was not only weather and distances which had to be overcome but also at times a hostile establishment. His good-humoured responses show a man of an exceptional steady disposition. The arrival of the Ordnance Survey in Kintyre during the 1860s may have passed long ago into local history, but Captain White's monumental drawings will remain as a testament to the determination and scholarship of this Ubiquitous Survey Sapper.

Cover illustration: Mull of Kintyre and Lighthouse, c 1866, from the sketchbook of Captain T. P. White in possession of the author, to whom thanks are due.

Sources and Notes

- 1. Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, Vol 8 1868-70, pp. 430-64, included White's 'Notice of the Priory Church of Beauly, Inverness-shire'.

- 2. This article resulted from the purchase at auction of Captain White's sketchbook by the author and subsequent research into his life. The sketches include several subsequently published.

- 3. Obituary Colonel T. P. White, The County Express, 25 October 1913, p 5.

- 4. Glasgow Evening Post, 17 July 1867, notice of birth of a son at Oban.

- 5. W. A. Seymour, A History of the Ordnance Survey, 1980, p 160.

- 6. Lieut.-Col. T. Pilkington White, R.E., The Ordnance Survey of the United Kingdom, 1886, p2.

- 7. Ordnance Survey website, open access.

- 8. Robert Brydall, Art in Scotland: Its Origin and Progress, 1889, p 398.

- 9. The Scotsman, 9 April 1873.

- 10. Western Morning News, 31 January 1894.

- 11. He died on 20 October 1913 at The Quarry House, Shrewsbury; his residence was given in the will as 3 Hesketh Crescent, Torquay, Devon.

- 12. Plates reproduced include 11B, Campbeltown Cross and 23 A-C, Kilmory and Keills, Knapdale, grave slabs. 10-0

Two letters, 1853 and 1854

Emigration-related letters seem to be turning into a

regular feature of this magazine and I welcome them and enjoy the

challenge of helping to elucidate the contents. These latest

letters were contributed by Mr Munro McCannell in Glasgow, whose

Kintyre connections will be explained later.

The first letter, dated 9 August 1853, was sent from Dunskeig,

Clachan, to Whitestone, Saddell. The sender was Charles Blair and

the recipients were his sister Jane and her husband Archibald

McCannell. Charles had emigrated to Canada but, for unknown

reasons, was back in Kintyre, an unusual move at a time when most

emigrants were never able to return home. He was recovering from

an illness, and the reference to his using burdock presumably

alludes to a medicinal tonic which his sister may have provided

him with.

The second letter is dated 15 December 1854 and was written at

Puslinch, Wellington, Ontario, whence he had returned in the

interval. The McCannells had also moved by then, but no great

distance: to East Killarow, Tangy, over on the west side of

Kintyre.

Most of the Blair family appears to have settled in Ontario and

married there. The Puslinch Historical Society website records

Charles's sisters' marriages: Mary to Malcolm Currie, Barbara to

Angus McCormick and Christina to Lachlan McMillan. Charles and

his brother John had parted company in 1854, John remaining on

the farm they had shared and Charles leasing a neighbouring farm.

The split appears to have been acrimonious. Their widowed father,

Archibald Blair, and sister Christina ('Christie') moved into the

new home with Charles. Both brothers had married by then, John to

Margaret Dunbar in 1853 and Charles to Agnes McMurchy in

1854.

The Blair and McCannell families both belonged to the Largieside.

Jane McCannell (remembered in the family as Sine, Gaelic for

Jane) was a daughter of Archibald Blair (1785-1863) and Mary

McDougall (1782-1850) and was said to be five months and two days

short of her hundredth birthday when she died at East Killarow on

8 March 1904. Her obituarist said she was born in Clachaig Glen,

Muasdale, but I have found no record of her birth, only that of

her marriage in 1827 at Muasdale. She had eleven children, of

whom eight were still alive in 1904. The Campbeltown Courier

(12/3/1904) remarked that 'Gaelic was her only tongue, for

although she could understand a little English, she was unable to

listen to or make herself understood by it with profit'.

Jane's having been a monoglot Gaelic speaker raises, once more,

the question of literacy. Her brother Charles, who appears to

have learned to read and write, was corresponding with her and

her husband Archibald in English, albeit fractured. Who was

translating these letters into Gaelic and composing replies to

them in English? Did one or more of Jane's children, who

certainly attended school, as censuses show, read out the letters

and reply to them?

The letters sent to Charles apparently do not survive, and the

survival of the two letters reproduced here was down to Jane's

having kept them; possibly, Munro thinks, because her eldest son,

Donald, who was born in 1827, was mentioned in the second one. He

had disappeared several years before, and the family never heard

of or from him again. There was speculation that he might have

gone to the Crimean War', but his fate remains unknown.

The John addressed on the last page of the second letter was

another son of Jane McCannell's. He must have spoken to his uncle

Charles about going out to Canada, and Charles provides

directions on how to reach his destination in Ontario from

Quebec; but he didn't go, and died in 1906, aged 72, at East

Killarow in his native parish. Charles also hopes that John is

giving up his 'foolishness', which can only be an allusion to a

fondness for alcohol.

Archibald McCannell and Jane Blair were Munro McCannell's

great-great grandparents. Their son, Duncan McCannell, ploughman

at Tangy, was presented with a Highland & Agricultural

Society of Scotland long service medal at the Kintyre

Agricultural Show in 1914, as reported in the Argyllshire Herald

on 13 June 1914. The medal, which Munro inherited, is dated 1913

and records thirty-seven years' service. He worked until the age

of 70 and died in 1933, aged 80. His widow, Isabella, a daughter

of Archibald Milloy, farmer in Breakachy, and Flora Downie, died

in 1948, aged 84, and was buried with him in Paitean. Archie

McCannell, Munro's grandfather, who was born in 1888, left East

Killarow circa 1904 and moved to Glasgow. His parents made no

effort to pass on the Gaelic language to their children, a

failing discussed in the last issue of this magazine (No. 91, p

16), and Archie recalled walking from Tangy to the church at

Bellochantuy on Sundays and having to sit through services

delivered in a language that was unintelligible to him.

Editor

Dunskeig August 9th 1853

Dear Brother & Sister I wrote these few lines to inform you

that I am a little Better in health and in good hope that I shall

get over it if it is according to his [God inserted above]

unering wisdom the rest of us are all well I have reason to be

thankful as I am, the rest of us are all well

I was mistaken in what I said to you about margret She is quite

well I received a letter from America three weeks ago, informing

me that they are all well, and spared as monuments of Gods mercy

I was very glad to know that Barbra [his sister] is well

and that she was Delivered of a Child being dead but she was not

long nor ill this time and she was quite well in a week after

that the doctor thought it was dead nine weeks before it was

born

I have also to tell you that John Got married to margret dunbar a

near neibhour of his own he saw they were willing in both sides I

received another letter from America last night from Donald

McMillan informing me of [a] Great many other marrieges that took

place

Since I left they had a very dry summer they had very little rain

since I left they comence the wheat 3 weeks ago the spring crope

is not very good they have no preaching since I left exept a few

days all the Congregation is going to join to buld one Church in

the midst of them two of the neibhours died and all others things

[are] as I left them

I hear that Christie and the young wife [of John's, Margaret

Dunbar] agrees well and I am glad of it they all join in

sending their best respects to you all they did not say any thing

more particular that I can mention to you at present

I did not see any of Archibald McDougalls family yet but I intend

to go and see them next week I would like you to write me back as

soon as possible so that I would Get it before I go over to see

them I Cannot say at present [when] I will be down your way to

see you I do not think that I will go home this winter if I will

not take another notion and tell John [McCannell, his

nephew] to be makeing ready to go with me next Spring if I

will wait and be both spared to that

I am useing the burdock since I came up write me without delay

and let me [know] how you are all geting along no more but

remains your affectionate

Brother

Charles Blair

Puslinch December 15th 1854

Dear Brother and Sister I received your letter a few weeks ago

and was glad of your wellfare only I was sory to hear of you not

being well We are all enjoying our health hear only Johns wife a

needle went into her knee six weeks ago and did not come out yet

She is very painful some times but she can walk through the house

mary [his sister, presumably] also she took a turn of

sickness but she is getting over it father he is quite strong

Barbra and her husband are well and my I was in good health

myself all this summer

I have to inform you that I got married six weeks ago to Agness

Mcmurchy Murdach Mcmurchys Daaghter [a family from

Kintyre] John and I parted at that time and I went on the

next farm to us bought the land from it belongs to the same man

that we at first I rented it for a year from him I am going to

try if he will sell it to me and if not I do not know wither I

will wait any longer on or not my father is in with me and

Christina from us in a good place She went there in the spring

She is hired nine miles John and I cast out and I would not let

her wait with them any longer and if it was not for that I would

not marrie yet and that is how I am situated in the mean time I

have great

This wourld is very Changable there is no trust to be put in an

arm of flesh so that ought to teach us to look to him Who is

unchangable reason to be thankful to God for his care over me

Since I seen you last and for the recovery of my health so far

Dear Sister this life is a life of trial I felt that since I left

you even my friends [were] growing cold to me but if you and me

was able to meet trials so as to overcome them By faith

everything would work together for our good I do not intend to

say much in this letter I do not feel well the day I have taken a

bad cold

I am at present driveind [driving] lumber with my own horses from

a sawmill I can make between two and three Dollars a day and some

times more but oats and hay are so very dear this year I have to

buy all the hay and oats I only got a share of the potatoes and

turnips and as much of the wheat as will do my own bread all that

came to my share when John and me parted [was] a pair of good

horses 5 years old a new wagon a sleigh a plough a harrow 2 cows

3 pig 3 Sheep and the half of the potatoes and turnips and some

other articles that belong to the house and two hundred and sixty

Dollars of money and my father is getting thirty Dollars a year

as long as he lives and Christina got nothing but some bet cloths

[bed clothes] but if I will be Spared I will not see

Christina in want

My father he speaks of going with barbra after this year I do not

know if I will be hear longer than till spring I would like to

get a place for myself if I could but land is so very Dear and

scarce it is not easy to be gott unless I would go back a hundred

miles in the woods and I do not like to go back farther than I

am

John Sold his farm for 28 Dollars an acre he is going to get

another crop of [off] the place yet every thing is very Dear this

year wheat is a Dollar and [a] half oats half a Dollar barley 3

and 9 pence a bushel 10 pence to 2 and 6 pence a bushel flour 9

Dollars a Barl [barrel] the same potatoes from 1 and pork is from

4 to 5 dollars a hundred[?weight] but we expect it to be oat meal

higher in a short time hay is 20 Dollars a ton and every thing

else accordingly wages a Dollar and a half in harvest a day and

15 Dollars a month through the summer season this is the best

year for farmers that has been since we came to canada and for

labouring men also there was a fair crop around this neigbourhood

the potatoes stands well

Dear Sister I must Draw to a close we got up a new church it was opened 6 weeks ago by our old minister Mr Meldrum [Rev William Meldrum, minister there from 1840 to 1853] the sacrement was dispensed at the same time we had one Mclean through the summer he left us and went to the collage and we have none at present

Dear John I wish to say a few words to you as you were speaking of coming to this country I would like very well to see you hear and I would do for you as a Brother and I hope you are giveing up your foolishness and as you were [asking] for me to write you how to come hear the only way for you to come is by quibeck [Quebec] and you can easy find the way from that to hamilton and the carrs are running from hamilton to Galt and their enquire for Mr young's tavern and tell him that you are a friend to John Blair and he will Derect you where to come

Dear John if Donald ever come or if you will ever hear from

him let me know I am glad that your father got a better place and

if I was able I would send home some monney to your father and

mother but I got nothing from John yet So that I had to ern what

monney I required for my marrage and before I got furniture for

my house and bought oats and hay for my horses I am a good Deal

in debt Dear John I will conclude by sending my love [to] you all

my father and all of them sends there best wishes no more at

present but remain yours sincerely

Charles Blair

'All tarred with the one brush'

The following colourful dialogue was reported in the

Argyllshire Herald of 25 September 1897, after the wife of a

Campbeltown labourer appeared in the Police Court accused of

committing a breach of the peace in Main Street, a charge she

denied. At the conclusion of the case, Bailie Duncan McWilliam

decided that the evidence was 'unsatisfactory' and that the

accused and the witnesses 'all appeared to be tarred with the one

brush'.

Accused (to the first witness) - Why is it you can't leave me

alone on the street?

Witness - Oh, because you wore silks and I never knew you.

(Laughter.)

Accused I never cursed and swore. -

Witness - Yes, you did.

Accused (throwing up her hands and sighing) - Oh, such a false

woman. I am here before my God a just sinner - (laughter) - and

all I called her was a 'town midden'. (Laughter)

Accused (to second witness) - Did I curse and swear?

Witness - You did that.

Accused - I never cursed and swore, gentlemen.

Witness - Well, I must be a liar then. (Laughter)